Guest Blogger: Stephanie Gibson, Curator Contemporary Life & Culture Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Many New Zealanders will remember the years of six o’clock closing of pubs. Urban pubs were often overcrowded, charmless places, where binge drinking took place in a race against the clock, resulting in the infamous ‘six o’clock swill’. Until the 1960s, alcohol could only be sold and consumed publicly in licensed places that provided accommodation. These were known as public hotels or ‘pubs’ for short.

In October 1917 New Zealand became the only country in the world to impose a nation-wide ban on the sale of liquor after six o’clock. Many believed that restricted access would result in less drinking. The ban lasted for 50 years until October 1967, when closing was brought forward to 10 o’clock by public vote.

Glassware, mid-1960s, by Crown Crystal Glass, New Zealand

(GH021024-25, GH023164, GH024221, Te Papa)

Standardised glassware was introduced by the Hotel Association of New Zealand (HANZ) in 1963. The 8 ounce glass on the far right was favoured by male drinkers. The smaller 7 ounce glass on the left and the small sherry glass were favoured by women drinkers. Jugs were considered an innovation in the early 1960s.

Until then, six o’clock closing dominated New Zealand’s social life. Drinking at the pub was mainly a male affair, with workers drinking as fast as they could on the way home from work between 5 and 6pm. Beer, the most favoured drink, was dispensed from plastic hoses (connected to a tank in the cellar) to speed up the process. Patrons could either drink at the bar, where their glasses were refilled by hose, or they could fill a jug and retreat to a standing table for a more leisurely intake. Pubs had little furniture in order to fit more drinkers in, and were lined with linoleum floors for easier cleaning which was often no more than a hose-down after patrons went home. Windows were frosted so that passers-by couldn’t see in and be tempted to drink. In practice, women could drink upstairs in more respectable private bars.

Some felt that early closing promoted poor drinking practices, while others considered it good for family life as it encouraged men to go home for dinner. Many believed that a worker’s leisure hours should not all be spent at the pub. The industry itself didn’t mind six o’clock closing because it meant shorter working hours. Staff were paid relatively well because of the limited number of pubs due to the restricted amount of licences available. However, in rural areas (particularly on the West Coast), six o’clock closing was widely disregarded as many workers had little opportunity to drink before six.

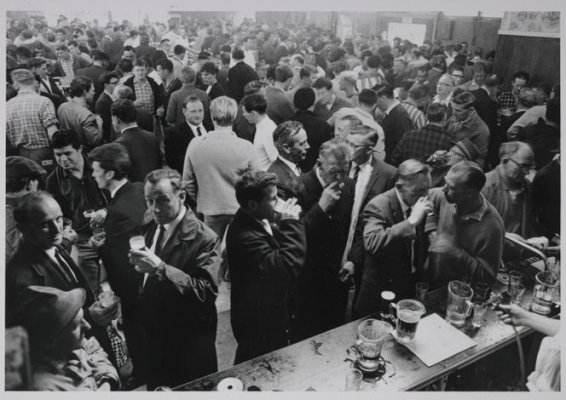

A crowd drinking at Porirua Tavern is captured on the last day of 6 o’clock closing in October 1967. Photograph by an Evening Post staff photographer. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington (PADL-000185)

The liquor licensing laws imposed extra restrictions on Māori and women. It wasn’t until 1962 that it became an offence to refuse to serve liquor on the basis of race. Women could not be employed in bars except for members of the licensee’s family and barmaids who were already employed when legislation was passed in 1910. Consequently, professional barmaids were very rare and rather elderly by the time this particular legislation was repealed in 1961.

The introduction of licensed restaurants in 1961 began to transform social life, enabling patrons to drink alcohol with food. The combined influence of New Zealanders travelling abroad, the arrival of new migrant groups and growing numbers of international tourists, helped to broaden gastronomic expectations and develop the wine-growing industry. From the mid-1960s there was an explosion of new restaurants in New Zealand’s larger cities, and in turn pubs began to upgrade their facilities. Floors were carpeted, seats provided and décor improved.

Since then, New Zealanders have seen a massive liberalisation of the drinking laws and associated culture – possibly the fastest such change experienced anywhere in the world. By the end of the century, more alcohol was available through more venues and longer hours, and to younger people.

This article originally appeared in Glory Days Magazine

Really interesting – I can’t imagine requiring pubs to close at six. Barbaric.

Thanks for sharing.

Barbaric is the word Bill. Thank you for checking out the Thirstyboys…

A similar history in Australia where it led to an escalation of domestic violence and child abuse. Terribly short-sighted legislation.

thanks for commenting Mike…we are hoping to post a few more beer histories.

What specifically was noticed to have increased DV and SA in Aussie?

[…] Thirsty Boys – Beer Histories: The ‘six o’clock swill’ […]